Treatment

- Low back pain affects at least 70% of population at some stage during their life

- In Australia, LBP is the single most frequent presentation to GPs

- The cause of pain is non-specific in 95% of patients

- Serious conditions are rare (but obviously need to be identified)

- Most episodes are self limiting :

- 90%+ substantially better within 2 weeks

- Episodes > 2 weeks affect only 14% of the population at some stage during their lifetime

- Majority of people with LBP make full recovery within 3/12, with some people experiencing exacerbations over time.

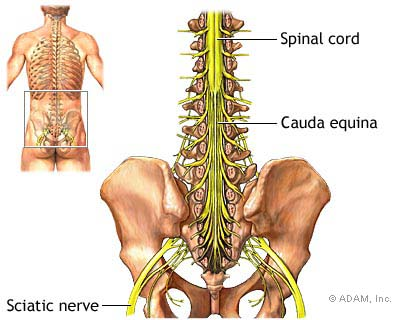

- The spinal cord terminates at the level of T12 / L1 and the cauda equina continues distally

- The cauda equina (“horse’s tail”) is the collection of lumbar and sacral nerve roots (lower motor neurones)

- Compression of the cauda equina can lead to Cauda Equina Syndrome, which is a medical emergency that includes some or all of the following:

- Urinary retention, faecal incontinence, lax anal sphincter, saddle area numbness

- Widespread neurological symptoms and signs in the lower limb, including gait abnormality

- Cause

- Cauda equina syndrome results from a herniated lumbar disk in 1-15% of cases.

- 70% of cases of herniated disks leading to cauda equina syndrome occur in people with a history of chronic low back pain

- 30% develop cauda equina syndrome as the first symptom of lumbar disc herniation.

- Males in their 30s and 40s are most prone to cauda equina syndrome caused by disc herniation.

- Most cases of cauda equina syndrome caused by disc herniation involve large particles of disk material that have completely separated from the normal disk and compress the nerves (extruded disk herniations).

- In most cases, the disk material takes up at least one-third of the canal diameter.

- Other causes include:

- Spinal Canal stenosis

- Spondylolisthesis (severe)

- Tumour

- Infection

- Severe trauma / swelling

- Infectious disease

- Failed surgery

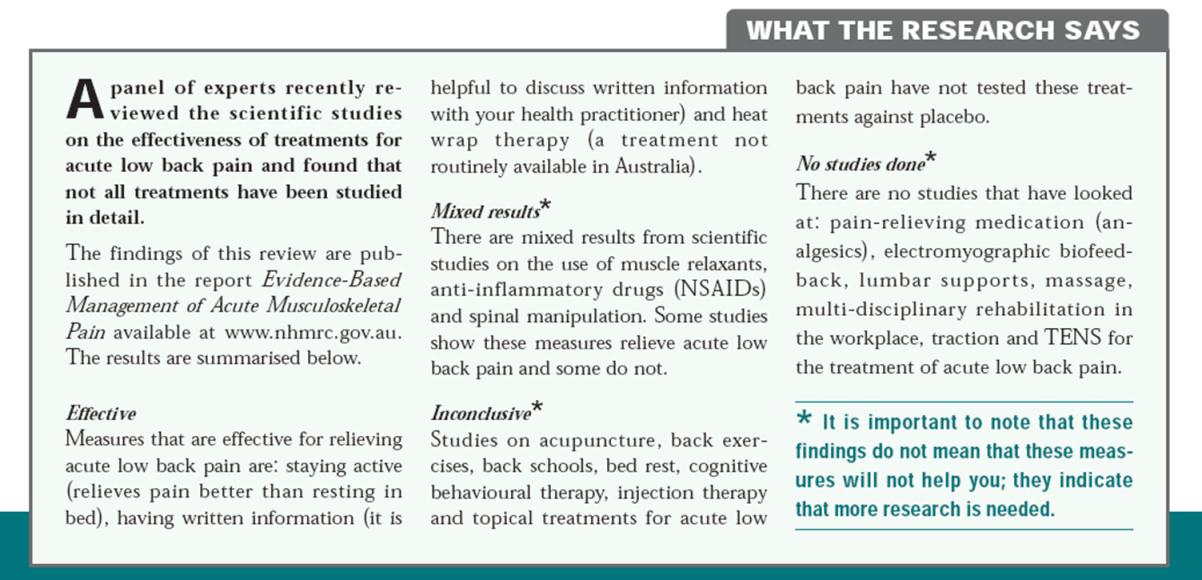

- For patients without Cauda Equina Syndrome and significant neurological dysfunction (ie significant loss of power, altered reflexes +/- gross sensory changes), there are many treatment modalities that are utilised, however not all are evidence based or have been shown in clinical studies to be effective

- The NHMRC (Australia) completed a systematic review of the literature for non-specific low back pain and a summary is found below:

Overview

NSAIDs Variability in risk of gastrointestinal complications with individual non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs: results of a collaborative meta-analysis.

Variability in risk of gastrointestinal complications with individual non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs: results of a collaborative meta-analysis.

- Usually, the primary reason a patient with LBP seeks assistance is for pain relief

- To treat a patient with acute LBP and expect to have them pain-free on discharge is as unrealistic as for a patient with an acute ankle sprain - pain is to be expected and is one of the mechanisms of the body to facilitate healing (to discourage you from doing things which are counter-productive in the initial stages)

- Ultimately, it is the body that facilitates healing - medications do not assist in this regard and there is some evidence that antiinflammatories hinder the healing process. After all, the inflammatory response after an injury CAUSES healing to occur, so we don't really want to meddle with this if we can avoid id.

- We need to reinforce that relief of pain should not be exclusively limited to pharmaceuticals = posture, positioning, relative rest and non-pharmaceutical methods of pain relief should also be utilised

- All drugs have unwanted side effects, so SHORT TERM GAIN VERSUS POTENTIAL FOR LONGER TERM PROBLEMS

- General health considerations are also important (see section later on)

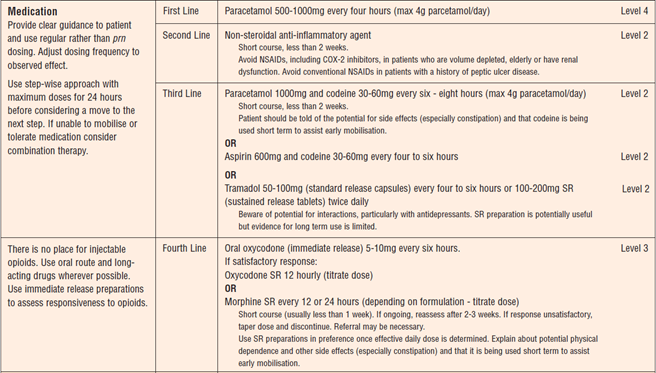

- The NSW Therapeutic Assessment Group (2003) devised the "Prescribing Guidelines for Primary Care Clinicians" for LBP:

NSAIDs

- Mode of delivery does not change potential problems (action is systemic)

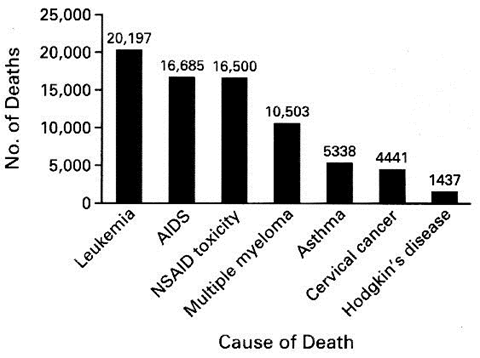

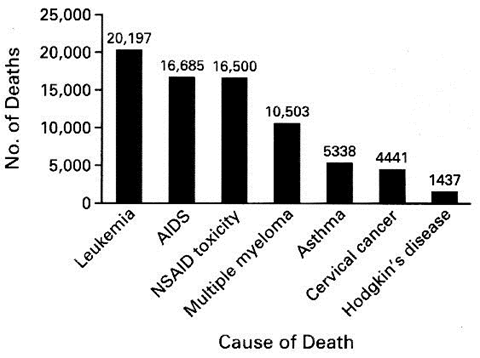

- U.S. Mortality Data for Seven Selected Disorders in 1997. A total of 16,500 patients with rheumatoid arthritis or osteoarthritis died from the gastrointestinal toxic effects of NSAIDs. Data are from the National Center for Health Statistics and the Arthritis, Rheumatism, and Aging Medical Information System

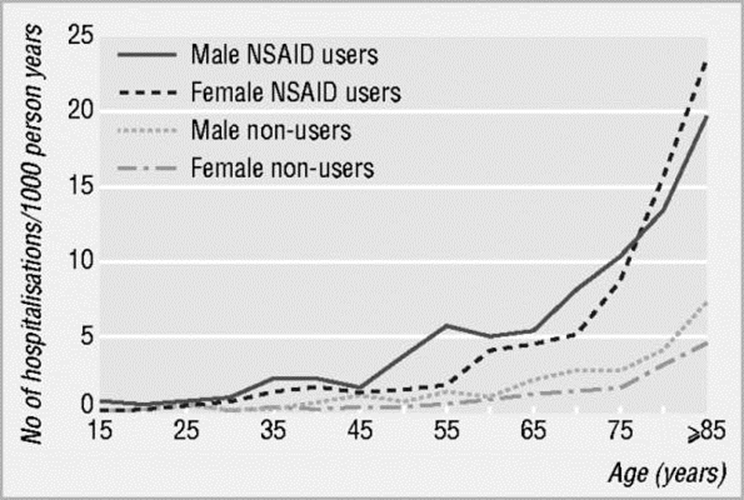

- Relative Risk of GI complications from NSAIDS

Variability in risk of gastrointestinal complications with individual non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs: results of a collaborative meta-analysis.

Variability in risk of gastrointestinal complications with individual non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs: results of a collaborative meta-analysis.

- Hospitalisations due to complications associated with NSAID use are a problem in elderly patients

- Complications

- Renal toxicity

- Interaction with other drugs (eg Warfarin, Corticosteroids, Diuretics, Antihypertensives, ACE inhibitors, Digoxin, Lithium, Aminoglycosides, Phenytoin, High dose methotrexate)

- NSAIDs have been shown to delay fracture, wound and soft tissue healing (Paracetamol shown to have similar effect as well, thought to work on similar COX pathways)

“Muscle Relaxants”

- BZDs often used for “muscle spasm” in LBP patients

- Lumbar muscle spasm not a defined pathology, usually a reaction to injury (body’s way of splinting self to avoid bending / twisting).

- Side effects = sedation (which sometimes is a good thing in anxious patients), decreased coordination, ataxia, memory impairment, amnesia, confusion, tolerance, dependence, addiction and withdrawal

- Long half lives (5-200 hours) – consider this especially in elderly

- Some evidence to suggest that is helpful compared to placebo or paracetamol in patients with LBP, but adverse events were significantly more prevalent.

Opiates

- Drugs of dependence

- Have some sedatory effect (respiratory depression in high doses)

- Constipation

- Postural hypotension

- Nausea / vomiting

- Miscellaneous CNS effects: euphoria, hallucinations, dysphoria

- “There still remains little evidence in the medical literature to address the concerns of physicians and patients regarding the effect of opioids on pain intensity, improved function and risk of drug abuse. The trials that do exist suggest that a weak opioid reduces pain but has minimal effect on function” – Cochrane Review 2007

Exercise

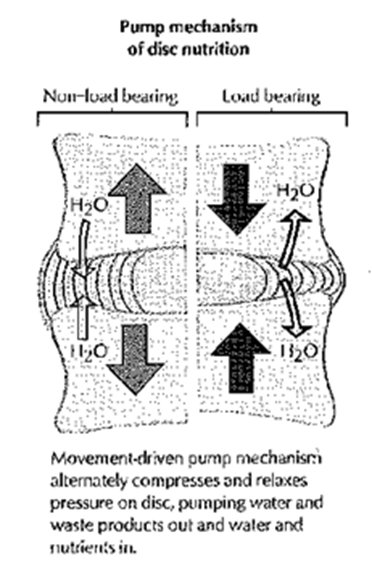

- Disc “Pump”

Exercise vs Bed Rest

- Acute LBP without radicular pain = small benefits in pain relief and functional improvement from advice to stay active compared to advice to rest in bed

- LBP with radicular pain = little or no difference

Exercise

- Little or no difference comparing advice to stay active, exercises or physiotherapy

Exercise on Prevention of Recurrence

- Evidence that exercises were more effective than no intervention in reducing rate of recurrence at one year, and 18-24 months

- Some low quality evidence that days on sick leave reduced at 18-24 months

Traction

- Strong evidence of no difference between traction and placebo, sham or no treatment

- Moderate evidence that traction is no more effective than other treatments

- Limited evidence of no difference in outcomes between standard PT +/- traction

Manipulation

- No evidence that better than any other treatment

Health Behaviours

- Need to consider general health

- Diet

- Exercise

- Obesity

- Lack of sleep

- Repetitive or dangerous activities

- Smoking

Smoking

- Human smokers approx 30% more likely to develop acute LBP and if have LBP, approx 30% more likely to progress to chronic LBP

- Rat studies show that even in passive smoking (2/52 of 5 mins of smoke exposure every hour during daylight hours), the nucleus pulposus exhibited fibrosis and hyalinization with disorganisation, cracking and breaking beginning to appear.

- After 7 weeks, histological changes were observed in 70% of nuclei pulposi and 75% of annuli fibrosi

- No changes at all were observed in the control rats

Education

- Patients receiving an in-person education session (2 hrs !!) in addition to their usual care had better outcomes.

- Shorter education sessions, or providing written information without an explanation did not seem to be as effective.

- Patients with chronic LBP were less likely to benefit than acute LBP

Treatment – General Principles

- Avoid activities which stress injured structures and aggravating factors (bending, twisting, sitting, driving / car travel)

- Keep straight for at least the first few days (lie, walk) but avoid prolonged bed rest

- Keep as active as possible (within limits) – walk frequently (may need to use crutches to assist in mobilisation) and gradually return to normal activity as able.

- RICE, avoid HARM in the acute stage (ice vs heat later; little in literature about ice for LBP, some evidence for heat wraps which provides short term relief)

- Regular analgesia (pharmaceutical and non-pharmaceutical) until pain settles – don’t expect to be pain free with medications (NB NSAIDs including paracetamol slow / delay healing, steroids are catabolic)

Low Back Pain Specifics

- Reassure patient

- Most LBP resolves quickly and without the need for surgery

- Provide education – evidence suggests that longer duration face to face education is significantly more effective than simply providing a pamphlet or brief verbal education

- Address Yellow Flags

- Avoid smoking – causes disc degeneration, increases likelihood of any injury (bony, skin, soft tissue) healing slowly or not at all

- Physiotherapy if persisting

- Large role in education

- Research shows that deep abdominals switch off and don’t function well without specific intervention to restore strength and timing

- Encouragement / support to be active with specific Lx as well as general exercises

- Can help to loosen stiff joints

- Encourage regular exercise